Integrating Traditional Knowledge and Science in EIA to Enhance Sustainable Energy Development

Greg Tyszko

Environmental Impacts Assessment and Traditional Knowledge

The Impact Assessment Act (IAA) was enacted by the Federal Government of Canada in 2019 and it has replaced the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (CEAA), 2012. One of the purposes of the IAA/CEAA is to ensure decisions are based on traditional knowledge, science, and other available sources of information. Section 35 of the Constitution Act (1982) affirms and recognizes Aboriginal treaty rights in Canada, as these treaties were negotiated between Canada and First Nations (Littlebear, 2009).

The Supreme Court of Canada has ruled in favour of Indigenous groups on a number of cases regarding Indigenous rights and the duty to consult. The R v. Guerin ruling in 1984 established that Aboriginal title was unique and the Crown had a fiduciary duty to protect these rights (Salomons & Hansen, 2009). This was followed by the precedent setting R. v. Sparrow decision in 1990, on Aboriginal rights, that led to the Sparrow Test to determine if the rights were existing, and if they were, how could the government infringe upon those rights (Salomons & Hansen, 2009). Outstanding questions regarding consultation were addressed in the Haida Nation v British Columbia. The Haida Nation was involved in a title claim to the Haida Gwaii Islands (Queen Charlottes) when the Ministry of Forests approved the transfer of a tree farm licence to Weyerhaeuser Company Limited (Raven, 2012). The Nation argued that without accommodation or consultation, by the time their title claim was decided upon the land and the forest would be cleared. The Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the Government of British Columbia had the legal duty to consult with the Haida, and where appropriate accommodate (Raven, 2012).

Incorporating traditional knowledge is not only a regulatory requirement for EIA but also an opportunity to develop a more collaborative approach with regulators, governments and proponents to share knowledge regarding energy projects and sustainability. Indigenous people’s experiential and scientific approach has served them well over the years, but very little work has been done to understand their connection to the environment and their ability to adapt to change. Traditional knowledge is an important and untapped resource that can provide scientists and decision makers with generations of experiential knowledge and a practical approach to environmental management. Traditional knowledge is a valuable tool that industry, regulators, and governments can use to clearly comprehend the message Indigenous people are trying to convey.

Traditional knowledge is culturally imbedded, has significant ethical and moral context, and understands the interconnectedness of cultural practices and the natural world. Traditional knowledge is empirical, subjective and qualitative, whereas science is analytical, reductionist, and quantitative. The biggest difference between traditional knowledge and science is that science isolates individual components of a study in controlled and simplified experiments, separating them from the complexities of the natural world. Traditional knowledge does not view the world based on linear conceptions of cause and effect but as constantly forming multidimensional cycles where all elements are part of a complex web of entangled interactions (Mazzocchi, 2006).

Traditional knowledge has evolved and provides a history of how changes have occurred over time including the impacts of climate change. This is an untapped resource that can help science develop a better understanding of man’s impact on the environment and how conservation management should be approached. For example, forest fire management has been practiced by Indigenous communities around the world and it is an important element of their land stewardship. Controlled burns were used to manage the buildup of combustible matter, pest control, creating grazing land, stimulate the growth of vegetation and creating fuel breaks around villages and camps (Indigenous Corporate Training Inc., 2019). This is in contrast to the slash and burn practice used by settlers to clear vast tracts of land for agricultural use, expose outcrops for geological surveys, and maintain railways. Weather conditions were not taken into consideration resulting in out-of-control fires. Governments responded with policies that focused on suppression instead of management which resulted in the buildup of combustible materials over time, allowing the fires to burn hotter and grow much quicker. This was very costly in terms of the economy, environment, and lives lost, both human and animal. In May 2016, the University of Royal Holloway London published a paper entitled Traditional Knowledge Could Hold the Key to Management of Wildfire Risk and the study used satellite imagery which suggested Indigenous lands had a lower incidence of wildfires in savannas and tropical forests (University of Royal Holloway London, 2016). When forests grow, they capture and store carbon and when they age, they become susceptible to environmental impacts like pollution, drought, fire, or pestilence which can be exacerbated by the effects of climate change. This is resulting in increased frequency of the disruptions to natural cycles and are adding carbon dioxide (CO2) to the atmosphere rather than removing and storing it.

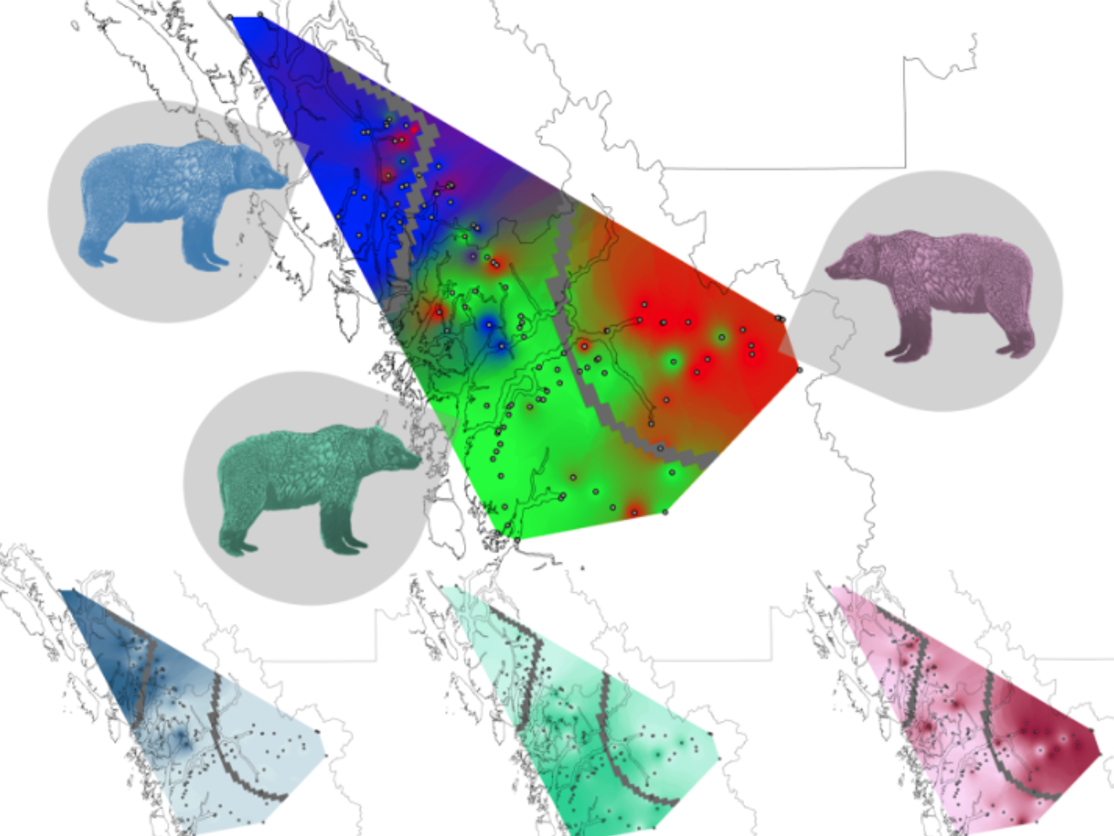

A recent study of bear genetics and traditional knowledge led to some interesting findings (Fritts, 2021). Researchers collected hair samples from bears along the central coast of B.C. and discovered there were three distinct genetic groups of bears in the area. Science suggests that natural or man-made barriers like mountains or large watersheds explains these genetic differences; however, these barriers did not exist in the area. When researchers examined traditional knowledge language maps, they found a geographical alignment with the three distinct genetic groups of bears. The traditional knowledge demonstrates that the area is rich in natural resources for both man and bear and therefore there was little need to migrate out of the area allowing the genetics of the bears and languages of Indigenous people to coexist in the same areas. Collaboration of science and traditional knowledge can provide both knowledge systems with a better understanding of the interconnectedness of nature, and in this case study, how biological and cultural diversity are intertwined (Fritts, 2021).

Fritts, 2021

Cumulative Effects Assessment and Traditional Knowledge

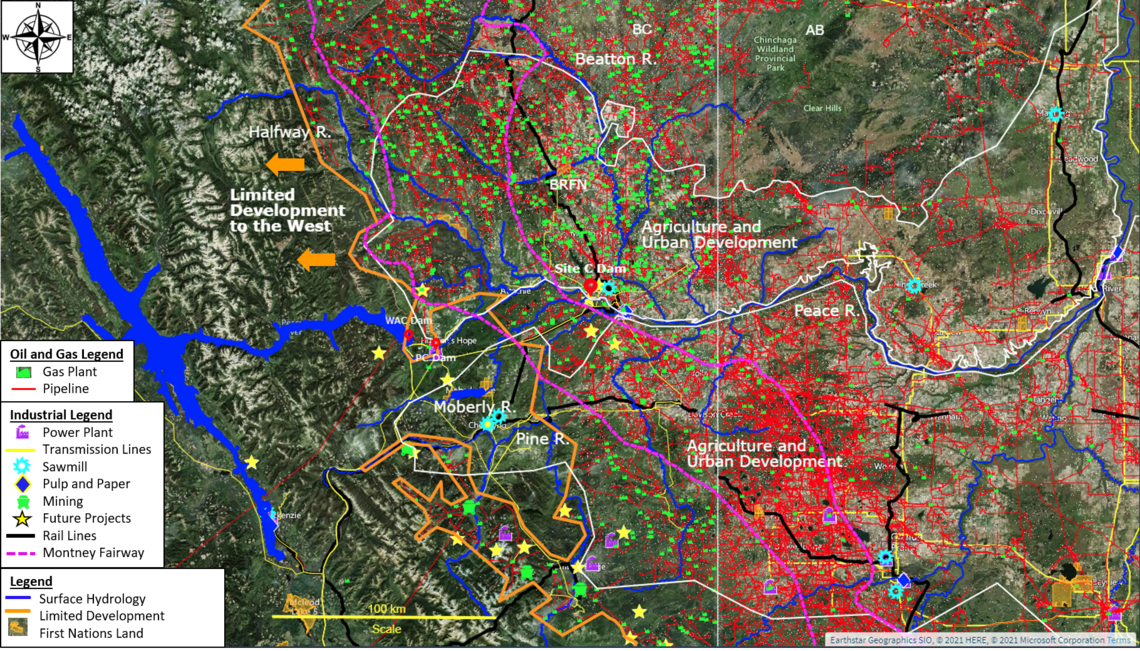

Cumulative effects associated with energy, industrial, and agricultural development have impacted Indigenous people’s traditional way of life. As an example, the Blueberry River First Nation (BRFN) recently won a cumulative impacts claim against the province of British Columbia. The B.C. Supreme Court ruled that the province breached its treaty obligations due to cumulative impacts of resource and industrial development and that there are no longer sufficient undeveloped lands available to exercise their treaty rights and live their traditional way of life (Prepost, 2021).

Understanding the interconnectedness of nature will be important for sustainable energy development. Indigenous communities are not often involved in energy infrastructure projects or have direct input into how these projects are developed; however, they must live with the impacts. They have observed environmental changes over time and can provide regulators, governments, industry, and scientists with their traditional knowledge on species and watersheds and the impact of energy development. Industrial and oil and gas development requires the building of access roads, large well pads, pipelines and facilities which impact the habitats of local flora and fauna and can result in pollution of streams with dissolved organic carbon, ammonia, total nitrogen, total phosphorus, and suspended solids. Indigenous communities rely on vegetation that grows in the riparian zone, and the fish and species that rely on the rivers for food and water. The impacts are not limited to oil and gas development but include hydroelectric projects, power plants, transmission lines, sawmills, pulp and paper, coal mining, renewable projects, rail lines and roads.

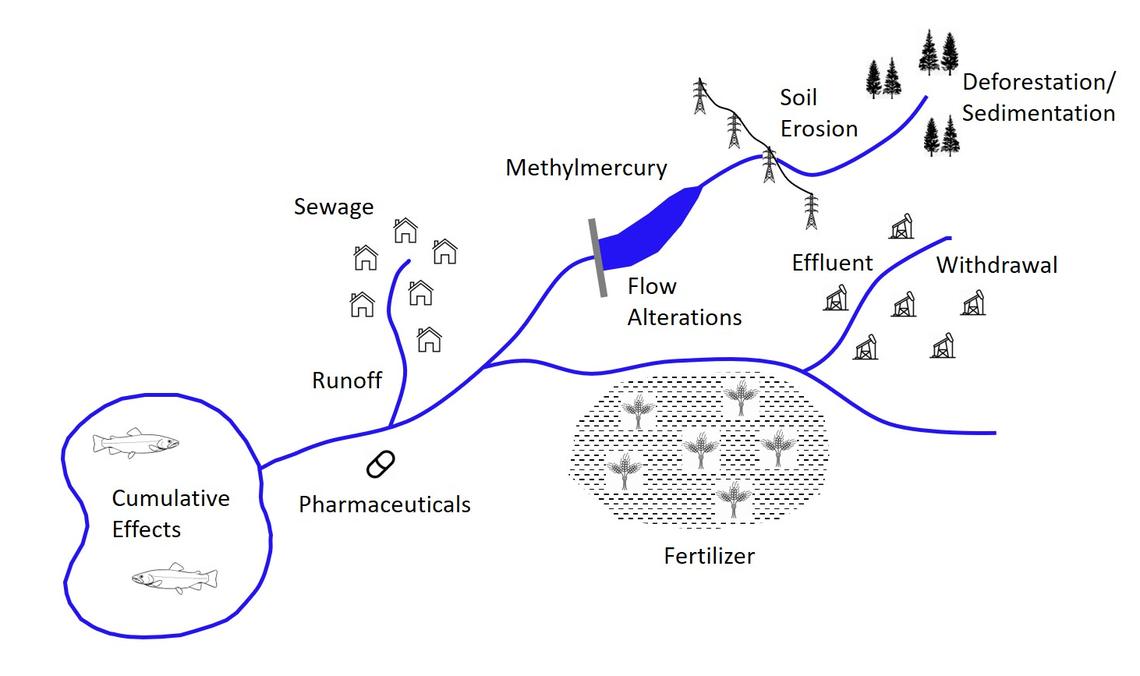

Cumulative Effects Assessment (CEA) is an approach to EIA that takes into consideration the multiple interactions of natural processes and human activities that accumulate across time and space. Individual projects may not have large environmental impacts but when considered with other actions of the past, present, and foreseeable future, may collectively have significant effects. Examples of cumulative effects include increased sedimentation due to soil erosion from transmission line crossings or deforestation, water withdrawals and discharges, oil and gas activity, runoff (sewage and fertilizer), and flow alterations from hydroelectric projects. All these effects will have impacts on the ecosystems and the species that rely on them and, in turn, will impact the ability of Indigenous communities to live their traditional way of life.

Cumulative effects mapping using geographical information systems (GIS) provides Indigenous groups and scientists involved in EIA and CEA with an opportunity to demonstrate the impacts of cumulative effects on all communities. This will provide decision makers with a visual representation of the impacts of development. Cumulative effects mapping using GIS are an effective way of representing the entangled interactions of resource development infrastructure and the impacts it has on the traditional territories of First Nations. The Peace River area is rich in natural resources and resource development will continue; however, governments and industry need to understand the impacts of development. Indigenous led studies would provide researchers with a unique perspective, based on a more holistic approach where acquisition of knowledge occurs over long periods of time and is indoctrinated in their culture. We are starting to see a cultural shift in society and environmental awareness is now part of mainstream consciousness and the public is becoming more vocal about government policy and corporate accountability toward environmental matters.

All Canadians have benefitted from energy development and fair and equitable opportunities need to be made available for Indigenous groups to participate in job creation, economic development, and sustainable energy development for their communities and generations beyond. Consultation with Indigenous communities should begin well before an EIA is submitted, they should be informed about ongoing operations, and project decommissioning to ensure their treaty rights are being protected. There is an opportunity for Indigenous groups, governments, and proponents to work collaboratively and share information regarding impacts to the environment, which should include Indigenous led studies and monitoring of VEC’s. Scientists are starting to understand the complexity and comprehensiveness of traditional knowledge and it is providing governments and industry with a different approach to analysing and understanding the biological and ecological complexity of the natural world.

Tyszko G. (2021)

(Tyszko G. 2021) based on Noble 2014

References

Fritts, R. (2021, August 13). ‘Mind blowing’: Grizzly bear DNA maps onto Indigenous language families. Retrieved from Science: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2021/08/mind-blowing-grizzly-bear-dna-maps-indigenous-language-families?fbclid=IwAR37SMSOCdIRZtco5oYhMbqj4x5-B9NpoYQQ5mGWFKvGTGSdTMfTKby0N00

Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. (2019, April 21). Indigenous Fire Management. Retrieved from Indigenous Corporate Training Inc.: https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/indigenous-fire-management-and-traditional-knowledge

Littlebear, L. (2009, July). Naturalizing Indigenous Knowledge. Retrieved from neatoeco: http://neatoeco.com/iwise3/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/NaturalizingIndigenousKnowledge_LeroyLittlebear.pdf

Mazzocchi, F. (2006). Western science and traditional knowledge: Despite Their Variations, Different Forms of Knowledge Can Learn from Each Other. Retrieved from National Centre for Beiotechnology Information: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1479546/

Prepost, M. (2021, July 2). Blueberry River wins cumulative impacts claim against B.C. Retrieved from Alaska Highway News: https://www.alaskahighwaynews.ca/fort-st-john/blueberry-river-wins-cumulative-impacts-claim-against-bc-3921547

Raven. (2012). Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests). Retrieved from Raventrust: https://raventrust.com/haida-claim-to-haida-gwaii/

Salomons, T., & Hansen, E. (2009). Sparrow Case. Retrieved from Indigenous Foundations: http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/sparrow_case/

University of Royal Holloway London. (2016, May 23). Indigenous knowledge could hold key to management of wildfire risk. Retrieved from Science Daily: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/05/160523104923.htm